Goya’s Black Paintings: Mental Illness & 19th-Century Art

Article by Katie Pittman

“The Last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns,” Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes was a 19th -century Romantic Spanish painter known for his representation of the everyday contemporary scene and later in life his dark tonal shifts into madness and mental illness (Art in Context). Goya began his artistic career in Saragossa Spain, studying under José Luzán y Martínez. His studies brought him to Rome in 1771, and after returning to Saragossa started painting frescoes in local Cathedrals. These frescoes garnered the attention of Anton Raphael Mengs, a German artist employed by King Carlos III. Mengs took Goya under his wing and helped him begin a career as a court painter.

In 1780, Goya was elected a member of the Royal Academy of San Fernando in Madrid, in 1785 he was appointed deputy director of painting at the academy, and the following year was given the title of painter to the King, Charles III, (Harris). Throughout this time, Goya’s work was that of aristocratic portraits, his style was conventional 18th -century poses and elegant finish and poise. As a royal painter, he did several famous pieces of Charles III and the royal family. This period in Goya’s career helped him to establish himself and build upon his skills and styles. However, this period came to an end with the death of Charles III in 1788. Goya continued to work for the royal family under Carlos IV until Napoleon forced the King’s abdication in 1808. Napoleon’s invasion would create a cataclysmic shift for Goya, bringing out for him the worst in mankind and surrounding him with cruelty and evil on all sides.

Mental illness in the 19th century was widely unrecognized as an illness, but rather an insanity or madness. Those who suffered from mental illness were hidden from society in an asylum, or as it was better known, a “madhouse.” In Europe, the modern asylum was born in the 18th and 19th centuries, with the belief that madness was curable through isolation. The average population in asylums continued to increase, with a spike during the middle of the century, ranging to over 1,000 patients, (Le Bonhomme). Depictions of mental illness were not humane, they often portrayed patients as monsters or creatures. Asylums were dark, dirty, and overcrowded, and accurately representing the chaos within was a spectacle for the rest of society to enjoy.

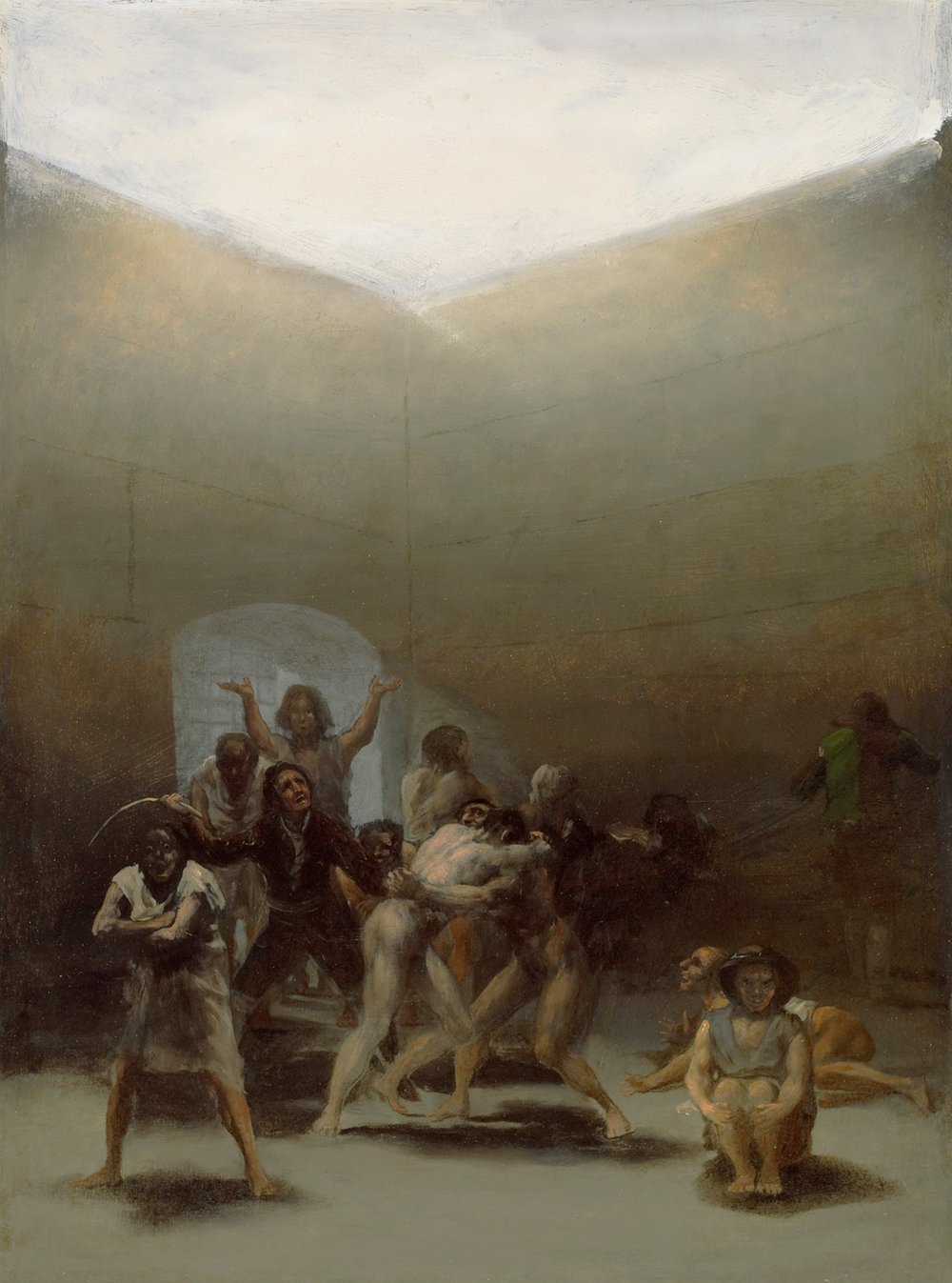

However, Goya differed in his beliefs, and frequently painted scenes of asylums and the mentally ill. In 1790, Goya painted Yard with Madmen, a compassionate view of mental deviance that was humane and progressive. He showed the darkness, the chaos, and the isolation, but managed to still reveal respect for those housed there. Asylums housed all who were deemed mentally ill, including religious heretics, murderers, thieves, and political dissidents. Goya did not portray these people as anything other than people within the walls of a dark place.

Figure 1: Yard with Madmen, Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes. 1794, Oil on tin-plated iron.

In 1793, Goya collapsed and himself suffered incapacitation and periods of illness and depression. These periods of illness lead to a gradual loss of hearing until Goya was practically deaf. He faced anxiety about his hearing loss which affected every aspect of his life. Once his hearing loss became an issue in the classroom, Goya was forced to resign from his teaching post at the Royal Academy. He sought multiple methods for curing his illness, but eventually resigned learning sign language. This loss heavily affected him, to the point where he retired from public life in 1819, and spent the next five years in a country home near Madrid known as Quinta del Sordo, The House of the Deaf Man. Ironically, while he was fully deaf at this time, the house was not named after him, but after the previous owner who was also a deaf man. This time spent in the country and at Quinta del Sordo marked a major shift in Goya, and his inner darkness began to come to the surface through his works.

Figure 2: The Third of May 1808, Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes. 1814, Oil on Canvas.

Before his hearing loss, Goya was surrounded by darkness and tragedy. The Napoleonic occupation deeply affected his psyche. He witnessed atrocities committed by French military and Spanish civilians during this time, remarking how both sides showed a blatant disregard for human life. Duty and desperation created such a strong emotional detachment that the horrifying consequences lost their meaning. Works created by Goya during the French and Spanish wars began to show the darkness that Goya faced internally. May 3 1808 is iconic for this period, and Goya depicts his personal feelings on the situation in the details. The central figure is martyred through his death, the lights and new technology are seen aiding violence rather than innovation, and the church in the background is dimmed out showing that the Catholic Church is insincere and ineffective in saving its faithful. This piece was not published until 1814 when King Fernando VII was restored to power, as Goya was fearful of being found and punished for the depiction.

Another series Goya created was The Fatal Consequences of the Bloody War in Spain against Bonaparte and other Striking Caprices, now known as the Disasters of War. These engravings were small but packed with intense details and gory depictions of the horror of war and the consequences Goya faced. This series marked a shift in Goya’s presentation of inner turmoil to the public, and the end of his public work.

While isolated in Quinta del Sordo, Goya began the iconic series of frescoes along the walls that were later named the Black Paintings. These works were never intended to be seen by the public, and only after Goya’s death were they viewed by anyone other than himself and his son. From 1819-1823, Goya worked on the Black Paintings, covering the walls with fourteen different pieces on the first and second floor of his home. These pieces were not titled by Goya only in 1828 when they were cataloged by Spanish artist Antonio Brugada were they given titles.

Since the discovery of the Black Paintings, there have been theories surrounding their interpretations, varying from subject matter to the validity of the works. The title of Black Paintings references not only the dark color palette, but also the dark underlying psychology to the work. Goya was painting for himself, allowing his thoughts to act out in the works. The paintings showcased different religious and mythological narratives and highlighted emotional states and Goya’s trauma. With emotions like anguish, loneliness, gloom, and satirical smiling and laughter, the pieces can be difficult for viewers to observe. Themes of death, aging, conflict, evil, and witchcraft are present throughout the pieces, however, there is no story or overarching theme that connects the works. Scholars have suggested that Goya’s deteriorating mental faculties, trauma, and harrowing experiences from the wars between France and Spain led to the darkness that surrounds each piece. Goya was able to express everything he thought and felt, and so he created a spectrum of emotion and the depth of the human psyche.

Stylistically, the pieces reveal similarities that run throughout the series: most figures are off-center, creating an imbalance that was modern for art of the time; most scenes lack light or are depicted at night time in the darkness. They showcase the ugly side of humanity both through actions and expressions - most of the figures are grotesque and distressed, yet have blissful or reflective expressions. The works recall nightmarish visions and evoke feelings of pessimism and dread upon viewing. It is said that this series was Goya’s experimentation and the beginning of expressionism.

Saturn Devouring His Children (1820), one of the darkest of Goya’s Black Paintings, is a history painting depicting the myth of the Roman god Saturn devouring his children. Saturn was plagued with the prophecy that he would one day be overthrown by one of his sons, so he swallowed each one whole though they remained alive and intact inside Saturn’s stomach, until the final child, Zeus, was able to rescue them and return them to the mortal world. Goya strays from this depiction and instead creates a cannibalistic and frenzied Saturn ripping apart his victim limb from limb.

Figure 3: Saturn Devouring His Children, Francisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes. c. 1820, Oil on Canvas.

Saturn is depicted in rough nakedness, with disheveled hair and beard, and a wide-eyed stare. These are attributes of a hysterical madman, with a dark aggression. He has already torn off and eaten the figure’s head, right arm, and parts of the left arm. His grip on the figure is so tight that his knuckles are white and bloody, The figure he is devouring does not resemble that of a boy or a man but is suggested to be that of a woman with rounded buttocks and a curving form. This raises questions as to whether this is an allegorical piece rather than the original mythological depiction. If this is an allegory, who does Saturn represent, and who is the victim? Scholars have suggested that Saturn might symbolize the autocratic Spanish state devouring its citizens, or that Saturn is the French Revolution and Napoleon’s wrath against the Spanish people. Saturn is a disturbing portrayal of conflict, fear, and bloodlust. He is primal and beast-like, showing the darkest elements of human nature.

Goya never intended for the masses to see these paintings.He used these pieces for cathartic expression, showing his inner musings and thoughts about his life and the events around him. By using the myth of Saturn and his children, scholars have tied Goya’s personal life and struggles with children to the myth and its depiction. Goya and his wife, Josefa Bayeu, struggled to have children. They suffered several miscarriages and together had eight children, with only one surviving into adulthood. In the myth, Saturn also has eight children, with the final and eighth child being the one to overthrow him and free the rest. It is possible that Saturn was a symbol of the loss and grief of Goya’s children.

In terms of visual elements and style used in this piece, the brushstrokes are loose and thickly applied, giving the piece physical texture. The wild use of texture and brush corresponds to the wild nature of the figure and subject. The figures themselves are misshapen, grotesque, animalistic, and abstracted almost beyond recognition. Saturn is bony, twisted, and animalistic, while his victim appears small and limp. Saturn lies on a diagonal line which contrasts with the vertical placement of his victim in his hands. The dark background highlights the central figures which could be interpreted as Saturn being caught in the act of a madman.

Goya was a troubled man in his later years. The decline in his mental health led to artistic creations that forced viewers into uncomfortably seeing the realities of the world. He is often seen as a man of delusions, and his private thoughts and musings created a vilification of his life and mind. Mental illness impacted Goya. Michel Foucault said it best when discussing the link between creativity and mental disorder, “We owe the invention of the arts to deranged imaginations; the Caprice of Painters, Poets, and Musicians is only a name moderated in civility to express their Madness,” (Foucault, Michel [1967]. Madness and Civilization, translated by Richard Howard).

REFERENCES:

Artincontext. “Francisco Goya ‘Black Paintings’ - Examining Goya's Dark Paintings.”

Artincontext.org, 15 June 2022, https://artincontext.org/francisco-goya-black-paintings/. “Black Paintings.” Black Paintings by Francisco De Goya,

https://www.francisco-de-goya.com/black-paintings/.

Facos, Michelle. An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art. Routledge, 2011.

Gowing, Lawrence. The Burlington Magazine 128, no. 1000 (1986): 506–8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/882587.

Symmons, Sarah. “Sacks, Giants, Owls, Cats: It's A Mad World in the Graphic Art of Francisco De Goya (1746–1828).” Forensic Science International: Mind and Law, vol. 2, 2021, p. 100061., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsiml.2021.100061.

Fanny Le bonhomme , Anatole Le bras , « Psychiatric institutions in Europe, nineteenth and twentieth century », Encyclopédie d'histoire numérique de l'Europe [online], ISSN 2677-6588, published on 21/10/21, consulted on 14/11/2022. Permalink : https://ehne.fr/en/node/14132

Katie Pittman is a Junior at Queens University of Charlotte majoring in Art History and Arts Leadership & Administration, with a minor in Interfaith Studies. She is originally from Columbia, South Carolina, and is an active member of Kappa Delta Sorority, working in a variety of leadership positions within her chapter. She hopes to pursue post-graduate education in Museum Studies in Chicago, New York, or Washington, D.C.